Last Updated on 22/01/2026 by Damin Murdock

A Practical Example from the Federal Court

In a late 1990s copyright dispute, two Australian amusement companies became embroiled in litigation over an unexpected subject matter: prize scales used in video draw poker machines. The case raised two important copyright questions. First, whether numerical tables could attract copyright protection at all. Second, how difficult it is to rely on the statutory defence of innocent infringement.

The dispute arose when one operator alleged that its competitor had copied prize scales used to determine payouts in electronic poker games. These scales consisted of numerical tables, setting out combinations and corresponding rewards. The alleged infringer argued that the material was too simple to be protected and that any infringement was entirely innocent.

Originality and Authorship

At first instance, the court accepted that the prize scales were original literary works for the purposes of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). While the individual numbers themselves were commonplace, the court focused on the selection, arrangement, and structure of the tables as a whole. That combination was sufficient to meet the originality threshold.

On appeal, the infringing party argued that the work lacked originality because it was derived from mathematical principles, and that the true authors were external mathematicians rather than the claimant’s employees. The appeal court rejected both arguments. It emphasised that copyright protects the work as a whole, not its individual components, and that collaborative input does not defeat authorship or ownership where the work is produced as a single integrated creation.

The Innocent Infringement Defence

The more significant aspect of the case concerned section 115(3) of the Copyright Act, which provides a limited defence for innocent infringement. Where established, this defence can relieve a defendant from liability for damages, although an account of profits may still be ordered.

At trial, the infringer succeeded in establishing this defence. The judge accepted that senior management did not know, and had no reason to suspect, that copyright was being infringed.

That finding did not survive appeal.

The appeal court made it clear that the defence imposes a demanding evidentiary burden. It is not enough to assert ignorance. A defendant must positively prove:

-

a genuine, subjective lack of awareness that the conduct constituted copyright infringement; and

-

that, viewed objectively, there were no reasonable grounds for suspecting infringement.

In this case, the infringer failed to lead sufficient evidence about the state of mind of its decision-makers at the relevant time. The court was not prepared to infer innocence simply because the material consisted of numbers or tables. Copyright protection applies equally to all categories of works, regardless of how mundane they may appear.

As a result, the appeal court overturned the innocent infringement finding and ordered the infringer to pay costs in both the appeal and cross-appeal.

Why This Case Matters

This decision remains instructive for two reasons. First, it confirms that originality can exist in functional or technical material, including numerical tables, provided there is sufficient skill and judgment in their compilation. Second, it demonstrates that the innocent infringement defence is narrowly construed and difficult to establish without clear, contemporaneous evidence.

Assumptions that “no one knew” or that the material was too basic to be protected are unlikely to succeed.

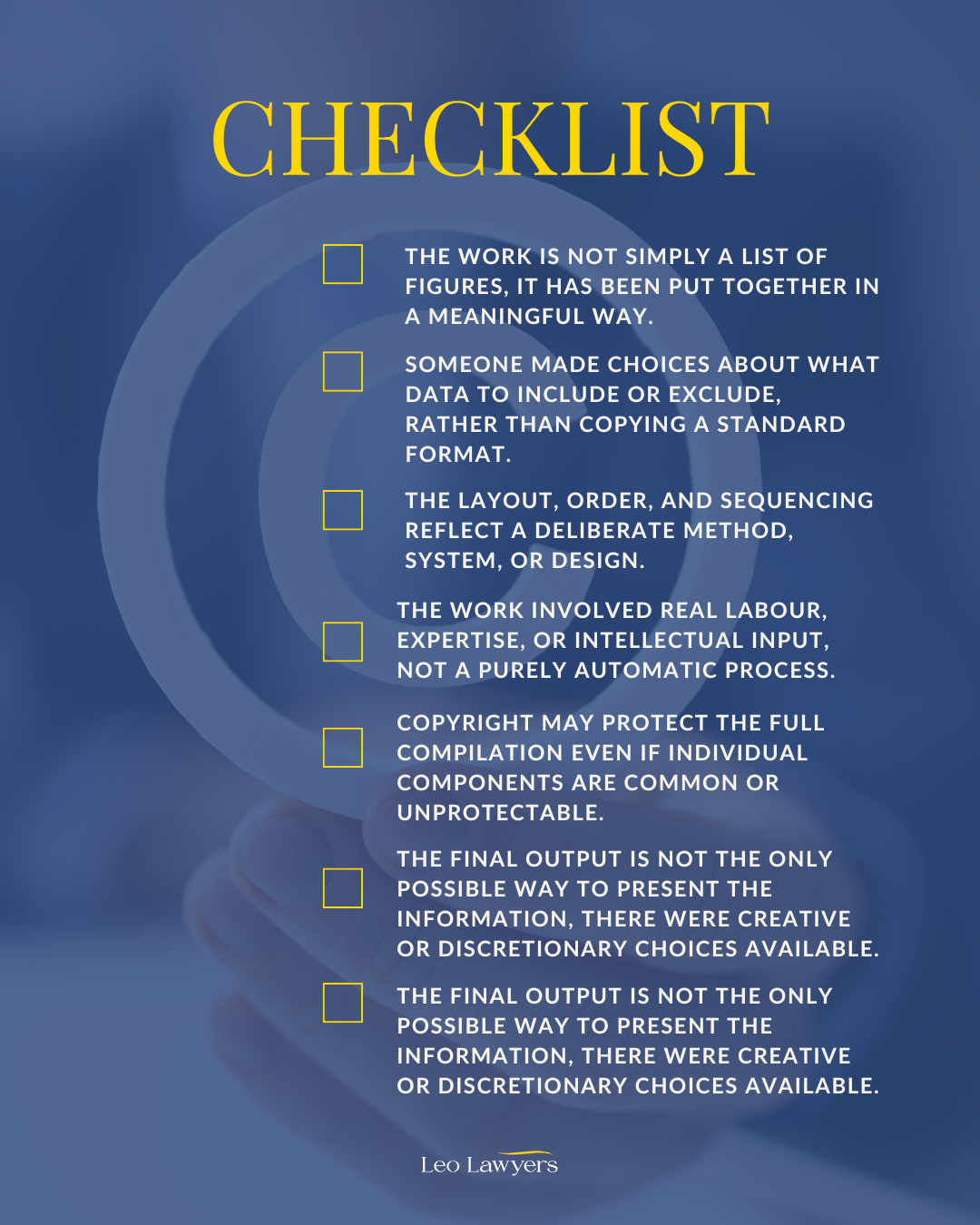

Originality Test Checklist

Use this quick checklist to assess whether a table, chart, or technical document may qualify as an “original literary work” under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth).

This image and its contents are protected by copyright under Australian law and international treaties. Leo Lawyers Pty Limited reserves those rights.

Practical tip

If you rely on tables, scales, templates, or other “functional” materials in business, assume they may still be protected if they reflect skill and judgment in how they are compiled.

Key Takeaway

To rely on the innocent infringement defence under section 115(3) of the Copyright Act, a defendant must establish:

-

an active, subjective lack of awareness that the conduct infringed copyright; and

-

that, objectively assessed, there were no reasonable grounds for suspecting infringement.

Absent compelling evidence on both limbs, the defence will fail, even where copying was unintentional.

If you work in licensing, enforcement, or compliance, or are concerned about potential copyright infringement exposure, early advice is essential. Please contact Damin Murdock at Leo Lawyers on (02) 8201 0051 or at office@leolawyers.com.au.

DISCLAIMER: This article is not to be taken as legal advice and is general in nature. If you require specific advice, please contact us.

Damin Murdock (J.D | LL.M | BACS - Finance) is a seasoned commercial lawyer with over 17 years of experience, recognised as a trusted legal advisor and courtroom advocate who has built a formidable reputation for delivering strategic legal solutions across corporate, commercial, construction, and technology law. He has held senior leadership positions, including director of a national Australian law firm, principal lawyer of MurdockCheng Legal Practice, and Chief Legal Officer of Lawpath, Australia's largest legal technology platform. Throughout his career, Damin has personally advised more than 2,000 startups and SMEs, earning over 300 five-star reviews from satisfied clients who value his clear communication, commercial pragmatism, and in-depth legal knowledge. As an established legal thought leader, he has hosted over 100 webinars and legal videos that have attracted tens of thousands of views, reinforcing his trusted authority in both legal and business communities."